- Home

- About

- Contact

- The CASEY BILL WELDON Page

- Mail Order

- The TAMPA RED Page

- Living Blues back issues

- Arkansas Blues compact discs

- BluEsoterica columns from Living Blues

- THE VOICE OF THE BLUES Page

- Mail Order Records: 78 rpm

- MBT

- The CHARLEY PATTON Page

- The OTIS RUSH Page

- BLUES HALL OF FAME Biographies

- The BluEsoterica Blog

- 50 Years of Living Blues

- The GABRIEL FLOCK-ROCKER Page

- LIcensing (Sync, Masters), Publishing & Research

The CASEY BILL WELDON Page

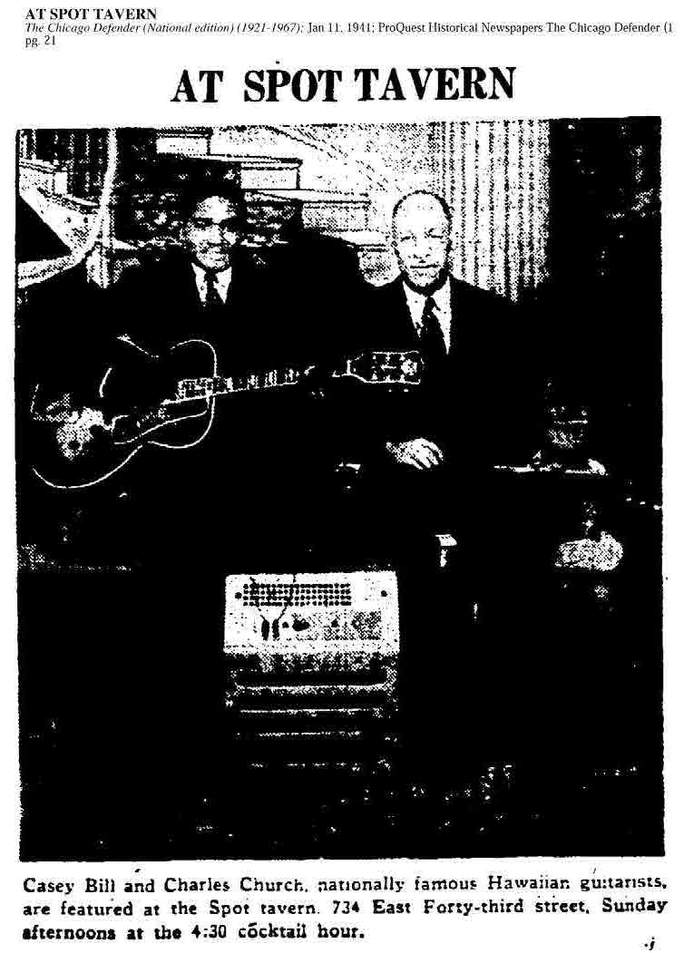

(In this, the only photo of Casey Bill Weldon we have come across, Casey Bill is the man on the right. The original caption from 1941 doesn't specify which guitarist is Casey Bill, but other ads in the Defender advertised Charles Church on Spanish guitar and Casey Bill on Hawaiian guitar.)

Press release April 10, 2015

HEADSTONE DEDICATION & TRIBUTE FOR CASEY BILL WELDON -- A COUNTERPART TO ROBERT JOHNSON

KANSAS CITY -- Casey Bill Weldon, a mysterious blues figure whose story is Kansas City's counterpart to the legend of Delta bluesman Robert Johnson, will be honored with a headstone dedication and tribute here on April 18 and 19. Weldon's grandniece, Los Angeles-based jazz/blues singer and educator CoCo York, is flying in for the dedication at Lincoln Cemetery on Saturday, April 18, and a "Tribute to Casey Bill Weldon" with other guest artists at B.B. Lawnside Bar-B-Q, 1205 E. 85th St., on Sunday. Both events begin at 2:00 p.m.

Weldon, like Johnson, wrote and recorded songs that have been covered countless times by blues, rock and jazz artists and even recorded for the same label as Johnson -- Vocalion -- during the same period, the 1930s. Tales abound of Johnson dealing with the devil; one of Weldon's songs was "Sold My Soul to the Devil." Weldon's music is included on the CD compilation "Roots of Robert Johnson." The two traveled in some of the same musical circles, including St. Louis, Memphis and Arkansas, and may well have known one another. Both helped pioneer new approaches to the blues. Weldon was unique not only in his instrument, the Hawaiian steel guitar, but also in ranking as possibly the first blues artist to have appearances on electric guitar advertised in the press. The dean of early European jazz and blues critics, Hugues Panassie, described Casey Bill’s music as “the purest blues imaginable.”

Tracing the two guitarists' lives and deaths has kept blues historians busy for decades. Both were known under several different names. The site of Johnson's grave was long disputed and headstones were placed in three different Mississippi cemeteries. But until the article "Unraveling Casey Bill Weldon -- The Hawaiian Guitar Wizard," appeared in Living Blues magazine in 2013 (see article below), the date (Sept. 28, 1972) and place (Kansas City, Missouri) of Weldon's demise had remained a mystery to the blues world. Weldon's headstone has been funded by a donation from Kansas City-based Folk Alliance International in coordination with Living Blues co-founder Jim O'Neal and the Killer Blues Headstone Project, with local assistance from Jason Vivone and Bob Suckiel (both musicians and hosts of KKFI radio programs), and other supporters.

Weldon's headstone is engraved with the introductory musical notes to his best-known song, "I'm Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town" (aka "We Gonna Move"), a classic that has been recorded by Ray Charles, Willie Nelson, the Allman Brothers, Louis Jordan, B.B. King, Mel Torme, Count Basie and many others.

Directions to Casey Bill Weldon's grave in Lincoln Cemetery (also the final resting place of Charlie Parker): From I-435, take exit 60, go east on Truman Road six tenths of a mile, go left (north) on Stark Avenue, which runs into Blue Ridge Boulevard. Continue north three tenths of a mile to the entrance to Lincoln Cemetery on the left.

This cemetery is in an unincorporated no-man's land between Kansas City and Independence called Blue Summit, in an area once called the Devil's Backbone. The residential neighborhood here is Dogpatch, once known as the home of motorcycle clubs and meth dealers.

More details to follow on CoCo York. For information, contact Jim O'Neal at 816-931-0383 or bluesoterica@aol.com.

CoCo York

**************************************************************************

UNRAVELING CASEY BILL—THE HAWAIIAN GUITAR WIZARD

By Jim O’Neal

Living Blues 228 (Dec. 2013-Jan. 2014)

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS (Living Blues #18, Autumn 1974)

Does anyone know whether and where Casey Bill is still living? Is he still active?

—Hugues Panassie, Montalban, France

Researchers and record collectors have long wondered what happened to Casey Bill, even before noted French jazz critic Hugues Panassie submitted the above query to Living Blues in 1974. Panassie himself (who died on December 8, 1974) was writing about Casey Bill in the 1950s, and in 1963 Jack Parsons wrote in an article in the third of issue of Blues Unlimited magazine: “In the absence of any positive data on his early life I can do little but attempt to reconstruct some of his activities . . . I prefer not to accept the reported death of Casey Bill.”

In a long-delayed answer to Panassie’s question, we can finally start assembling the biographical puzzle of Casey Bill Weldon, “The Hawaiian Guitar Wizard,” who died in 1972. The puzzle is still missing some big pieces, but at last we have solved some details of his family history, his death, and his burial site. After collaborating for several years with Australian and British research hounds Bob Eagle, Tony Russell, John Newman, and others, I found that many of the answers lay within a few miles of my house in Kansas City; even my children’s school became a source of information.

Weldon was a pioneer of electric guitar in the blues and made some of the most distinctive blues records of the 1930s, ranging from hard-time blues to good-time hokum. (“Weldon’s work,” Stephen Calt and John Miller observed in the liner notes to the Yazoo LP Bottleneck Trendsetters of the 1930’s, “is an outright rejection of traditional blues harmony, and invites comparison to western swing . . . He may well have influenced such white slide guitarists as Leon McAuliffe, the steel guitarist for Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys.”) He composed and recorded the classics We Gonna Move (To the Outskirts of Town), W.P.A. Blues, Somebody Changed the Lock on My Door and Back Door (a.k.a. Tell Me Mama), and his Go Ahead, Buddy was reissued on Yazoo’s Roots of Robert Johnson collection. (Weldon’s Sold My Soul to the Devil also suggests a theme he and Johnson may have had in common.) But after he made his last records in December 1938, scant evidence ever surfaced as to his whereabouts. The January 11, 1941, Chicago Defender printed a photo of him when he was appearing locally at the Spot Tavern with another Hawaiian steel guitarist, Charles Church; Big Bill Broonzy wrote a brief bio—the only such source on Weldon for many years to come—in Big Bill Blues (published in 1955): “I also played with Casey Bill on the WPA Blues that he recorded. His real name is William Weldon. He was born in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in 1909, July 10, and he’s in California now.”

The only update transmitted to the blues world in subsequent years was a statement in the Calt/Miller Yazoo liner notes that Chicago guitarist Ted Bogan “saw him locally in 1968. At that time, Bogan reports, Weldon lived in Detroit.”

More recently, blues author Guido van Rijn has postulated that Casey Bill was the steel guitarist on Cecil Gant’s 1945 Los Angeles recording of Little Baby You’re Running Wild, a possibility since Broonzy had placed him in California and by that time there seemed to be no trace of him in Chicago. Even anecdotes from other Chicago musicians about Casey Bill are in short supply because the great wave of bluesmen from the Deep South arrived only after he had apparently left town. Blind John Davis, who moved to Chicago in 1916, did recall Casey Bill, usually in the context of bluesmen he deemed difficult to work with in the studio or rehearsals (a group that included Washboard Sam and Jazz Gillum). In a 1977 interview, he said, “And what is this other crazy guy, he played this Hawaiian guitar? Casey Bill, yeah. Oh, man. Oh, you just couldn’t get along with him. He’d play a song right today, he’d come back tomorrow, he done changed it. And I’d be done wrote it out, you know. I said, ‘Well, man, I got it here, wrote out.’ ‘Well, I don’t know how you got it like that.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ And we wound up, he come right back to what I got wrote out. I just let him alone. He come back.” In 1976 Davis described him this way: “He was another crab with that Hawaiian guitar, Spanish guitar. But I’d cuss him out and he’d come on down.” As for the guitar playing, Davis said, “I didn’t care too much for it.” Paul Swinton, publisher of the Frog Blues and Jazz Annual, adds that Casey Bill had connections in the jazz world: “Fats Pichon was supposed to be a mate of Weldon’s. The Fats Pichon reference was made to me by a guy called John L. Thomas that I interviewed and had a brief correspondence with in the early ’90s. He also told me that Weldon performed together with Laura Rucker and Franz Jackson.”

The Weldon identity issue has been complicated by the widely held assumption that William “Casey Bill” Weldon was the same person as guitarist Will Weldon, who recorded for Victor in 1927 and did several sessions with the Memphis Jug Band. Will Weldon’s likeness, taken from a Memphis Jug Band photo, appears on some Casey Bill albums and in the recent book African Americans of Pine Bluff and Jefferson County hailing Casey Bill as a native son. But I found a death certificate for Will Weldon, a 28-year-old musician residing at 205 Beale in Memphis, on the Shelby County website. He “died suddenly from an attack of acute indigestion” on April 30, 1934, a year before William Weldon made his first record under the name Kansas City Bill Weldon—shortened to Casey Bill on later records. Will Weldon of Memphis was born in Grenada, Mississippi, according to the death certificate, and in the 1930 census he and Memphis Jug Band icon Will Shade were living in the same house in Memphis.

Another widely circulated story was that Casey Bill was once married to, or had a relationship with, Memphis Minnie in Memphis before Minnie married Joe McCoy on February 20, 1930. This item goes back to a 1970 Blues Unlimited article by Mike Leadbitter, based on a visit with Minnie and her family by Leadbitter and Memphis record collector Fred Davis. Leadbitter wrote: “Back in Memphis she became the common-law wife of Casey Bill Weldon (no one remembers exactly when) and he helped her a great deal with her music. He was a member of the Memphis Jug Band and was a lot younger than Minnie.” What is not clear in retrospect is whether the name Leadbitter heard was Casey Bill Weldon, or Will Weldon. But since Will was thought to be Casey Bill anyway, it became part of the Casey Bill biography. There seem to be no marriage records of Minnie to either Weldon, but considering Will Weldon’s Memphis connections it seems more likely that Will Weldon, and not Casey Bill, was Memphis Minnie’s man. Will was also several years younger than Casey Bill turned out to be. Big Bill wrote about both Casey Bill and Minnie but never mentioned that they had been married. A few Internet sites are now reporting that there is some evidence that Casey Bill married Geeshie Wiley, who recorded for Paramount in 1930–31 and then seemed to drop from sight much as Weldon did. But I know of no such evidence and no connection between the two other than the mystery and obscurity of their biographies.

But Casey Bill did know Minnie, as he played on a session with her in Chicago in 1935. And on his 1938 recording of Way Down in Louisiana, Casey Bill sang, “Memphis is my home, that’s way down in Tennessee.” In a 1969 issue of Blues World, Big Joe Williams told Richard Noblett that Casey Bill was from Brownsville, Tennessee. And to add another possible city of residence to the Casey Bill list, it’s worth noting that on the day of his first session, March 25, 1935, he recorded in the company of two East St. Louis bluesmen, Peetie Wheatstraw and Blind Teddy Darby. The influence of Wheatstraw is obvious in Casey Bill’s singing and “ooh well well” vocal mannerisms.

Sorting out the two Weldons was not the only issue about Casey Bill’s name. It turns out that he had two names, as verified by funeral home, cemetery, and state of Missouri death records. The trail to discovery began with a Social Security Death Index entry for William Weldon, born in Kansas on February 8, 1901, who applied for Social Security in Illinois, with a last address in Kansas City, Kansas, and a death date of September 1972. On his original Social Security application, filed in Chicago on August 17, 1939, Weldon gave his birth date as February 1, 1902, and the place as Schenute [sic], Kansas—in all probability Chanute, a town southwest of Kansas City at the junction of two railroads well known in song lore, the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (“the Katy”) and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe. His parents’ names were entered as Jacob Weldon and Caroline Hamilton and his wife’s as Luetta Johnson. The release of the 1940 census files in 2012 provided enough evidence that this was the same William Weldon, a musician, age 39, married to “Louetta,” at the same Chicago address, 445 E. 41st Street. Again he claimed a Kansas birthplace, and stated he had attended school through the eighth grade. The census asked where he and his wife were living in 1935; for Weldon it was “same place” (Chicago), and for his wife, Ozark, Arkansas. A 1930 census entry for a black William Weldon, age 29, also born in Kansas, seems to match, even though it was in Concord, Indiana, at a Wabash Railroad construction camp. Weldon’s occupation was listed as laborer for the railroad, while his father’s birthplace was given as Texas and his mother’s as Virginia.

The data from these documents unfortunately created more confusion when trying to trace the rest of Casey Bill’s path. In fact, some of it now seems either strangely inaccurate or intentionally misleading. Searches for Weldon and his parents in pre-1930 census files, in Chanute city directories, and in the birth, obituary, and cemetery records at the Kansas State Archives in Topeka, came up empty. For the record, both Chanute and Ozark, Arkansas, have always had minuscule African American populations. The pairing of a Texas-born Jacob with a Virginia-born Caroline did not produce search results either.

Although there was no notice of his death published in Kansas City, Kansas, I decided to scroll through microfilm of the Kansas City (Missouri) Call, since it was the only local paper that regularly published obituaries of African Americans in 1972. And there, finally, was an inconspicuous three-sentence obit:

WELDON, Williams [sic], 2325 Troost, passed away September 28. Services will be held Saturday, October 7, 11 a.m., at the Watkins Brothers Memorial 18th St. chapel with the Rev. A.M. Lampkin officiating. Interment in the Lincoln cemetery.

Conversations with the funeral chapel and the cemetery provided the name of a family member—a nephew, Charles Hammond—and the revelation that they had two names in their files for the deceased: William Weldon and Nathan Hammond. Weldon’s last address was on the Missouri side of K.C., on a stretch of Troost Avenue that has since been rebuilt into an overpass with no sign of the apartment where Casey Bill lived. A State of Missouri death certificate verified that Nathan Hammond, a.k.a. William Weldon, was a “retired musician” who died at General Hospital of “undetermined, apparently natural” causes. His birthdate was listed as February 2, 1901, and his parents’ names, as given by the informant, Charles Hammond, were Jacob Hammond and Caroline (unknown maiden name).

Pursuing the Hammond trail, I found that Charles was born in Plumerville, Arkansas, on September 12, 1926, and was a member of the Kansas City musicians’ union. On his 1957 membership application he indicated that he played at the Cuban Room on Linwood Boulevard and listed his instruments as piano, bass, and accordion and his other trades as broom maker and piano tuner. Local city directories listed another occupation for him—cigar vendor at the main post office, and that’s how he is usually recalled by locals. The Kansas City Star ran an article on him on May 29, 1949, upon his graduation from Lincoln Junior College, noting that he had attended the Missouri School for the Blind and hoped to work as a teacher or in social service with the blind. Lincoln was a small two-year college that was housed in the same building as Lincoln High School, which happens to be the school my children attend. The school librarian found a yearbook from 1949, and in it was a class photo of Charles Hammond and another shot of him with the junior college choir. He died on May 9, 1994, and was buried without a headstone in Blue Ridge Lawn Cemetery in Kansas City. The cemetery has no family contact information, and the companion who was mentioned in his obituary, Eugenia (Jean) Eddings, died in 2000. Hammond’s obituary listed two surviving sisters, Idella Davidson and Mozella Hammond of Chicago, and a brother, Dorsey Hammond of Bakersfield, California.

The Hammond family showed up in many census records and other documents, including family trees posted at ancestry.com by various descendants, although there was very little about Nathan. As reconstructed from these records, Jacob Hammond, a farmer (born July 1856), and his wife, Sarah Caroline Hammond (May 1858), were born in South Carolina, where they were listed in the 1880 census in Fairview Township, Greenville County. They moved with their children Keifer Finton and Dona (or Donie or Donnie) to Arkansas before the December 1883 birth of another son, William Ernest. The Hammonds’ Arkansas home base in the census was Union Township in Conway County; family trees and other documents cite Plumerville, Springfield, and some other communities in the same county, northwest of Little Rock. (Pine Bluff doesn’t seem to figure into the family history.) In 1896 Jacob became the owner of 80 acres by land grant. By 1900 Caroline had had ten children, eight of them still living, and she subsequently had two more, Nathan and Florida. Jacob died prior to the 1910 census, when Nathan, age nine, was shown as one of seven children living with Caroline on Plumerville Road in Union Township. Two of the Hammond children married members of the Criswell family, which had also relocated to Conway County from South Carolina. Among the many other black former South Carolinians who settled in Arkansas during a post-Reconstruction migration was a William Weldon (born c. 1872) in Woodruff County—whether he fits into the Hammond story is another question. Through conflicting documentary entries and varying family usage, the name Hammond has also appeared as Hammonds, Hammon, and Hammons, and Criswell has been rendered as Chriswell and Christwell.

While some of Casey Bill’s brothers remained in Arkansas to farm, at least four of his siblings moved to Kansas City, some on the Kansas side (KCK) and some in Missouri, probably beginning with Dona and her husband John Criswell around 1917. Charles Frank Hammond Sr. followed, and it was his blind son Charles who tended to Casey Bill’s funeral and burial. Dona’s son Theodore Christwell was a well-known barber and civic leader in KCK and once operated the North End Tavern from the rear of his barbershop on 5th Street. Casey Bill probably lived with one Hammond/Criswell family or another at times, but it has been hard to document his presence either as Nathan Hammond or Weldon in K.C. in city directories. He could be the mechanic William Weldon who is listed in 1965 and some later directories. But he seems to have left little trace locally, and the Hammond-Criswell descendants I have contacted knew nothing of him other than as an early figure on the family tree. There are no files under either of his names in the surviving Kansas City musicians’ union records of the State Historical Society of Missouri (nor in the St. Louis, Los Angeles, or Chicago union archives). Local archivist and deejay Chuck Haddix, co-author of Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop—A History, says he has never come across any local references to Casey Bill in his research, which includes a detailed log of musical news from the Kansas City Call and other newspapers.

However hazy it may appear, the Kansas City connection makes sense for Casey Bill, not only because of his nickname, his family in K.C., and his death here, but also because of his instrument. The steel guitar, introduced by Hawaiian musicians, was further popularized by western swing outfits in the southwest and was also adapted by several jazz/blues orchestras with roots in the region, most notably Andy Kirk’s Twelve Clouds of Joy. Kirk’s recording of Floyd’s Guitar Blues, featuring Floyd Smith on amplified steel, was an influential hit in 1939. It is rightly hailed as a groundbreaking work in the history of electric blues, but it was recorded on March 16, 1939, three months after Casey Bill plugged in his steel guitar on his final session for Bluebird on December 16, 1938, at the Leland Hotel in Aurora, Illinois. (Guitar historian Jas Obrecht has determined that Tampa Red also used an amplifier at his Bluebird session that day; there were a few earlier blues sessions with electric guitarists including George Barnes. John Newman points out that an electric steel guitarist--Casey Bill?--also recorded with Curtis Jones on September 27, 1938.) And some of the development of electric guitar took place in areas familiar to Casey Bill: while Los Angeles was a prime center, Kansans take pride in the claim that the first public performance on electric guitar was in Wichita, when Gage Brewer played both Hawaiian and standard guitars with amplification, as documented in the Wichita Beacon of October 2, 1932. Eddie Durham was one of the first jazzmen to record electric guitar solos, including tracks with Jimmie Lunceford on September 23, 1935, and with the Kansas City Five on March 18, 1938. Durham claimed to have passed on some of his electronic know-how to Floyd Smith, T-Bone Walker and Charlie Christian. Meanwhile, the earliest advertisement I have seen for a blues artist performing on electric guitar appeared in the Chicago Defender on November 27, 1937, for a show at Doc Jennings’ 33rd St. Cafe featuring none other than Casey Bill. (See update below for an earlier ad.)

The Casey Bill story still has huge gaps and big questions. When and why did he start using the name William Weldon? Was he born in Arkansas or Kansas? Did Nathan Hammond invent a new persona and bio for himself as did his friend Lee Conley Bradley (who became Big Bill Broonzy and also denied his Arkansas birthplace)? Were there legal reasons he chose to use another name? Did he have more than two names? Did he record music for film soundtracks, as Sheldon Harris suggested in Blues Who's Who? Who were the hot guitarists who joined him on his recordings with the Brown Bombers of Swing? Where was he during all the years after he was pictured in the Chicago Defender in 1941? California and Detroit possibly, but that information is second hand. Maybe Tennessee—at least one brother, Charles Sr., had some connection to Trezevant, Tennessee, in the same part of the state as Memphis and Brownsville. And a guitar/banjo player named Howell Hammons (aka Banjo Ike) was a member of the K.C. musicians’ union from 1946 to 1948; he gave Trezevant as his birthplace and his birthdate as January 1, 1908. He was also listed, as Howell Hammonds, in the 1935 K.C. city directory as a musician. Howell must have been related somehow and maybe this was even Casey Bill in another disguise, borrowing a name from a guitarist/banjoist he must have known in Chicago, Banjo Ikey Robinson (who may have appeared on some of Casey Bill's records). Chuck Haddix, however, reports no sightings of Howell in his K.C. research. There have been William Weldons and occasional Nathan Hammonds in various city directories across the country, but none we have found listed as a musician. What we do know for sure now is that he is buried in a grave with no headstone in Kansas City’s Lincoln Cemetery, famed as the resting place of another musical pioneer, Charlie Parker, way on the outskirts of town.

Various Hammond(s) and Christwell family members, including Cheryl Christwell and Charles Harris, have posted info at ancestry.com, and we hope their families can help fill in more of story. If any LB readers have information to contribute, please e-mail me at bluesoterica@aol.com. A headstone for Casey Bill is also on the LB agenda.

Thanks for research assistance to Brenda Haskins, Bob Eagle, Tony Russell, Paul Garon, John Newman, Paul Swinton, Rob Ford, Chuck Haddix at UMKC Marr Sound Archives, Chris Smith, Guido van Rijn, Cheryl Christwell, Charles Harris, Mike Pettengell, Horace Washington, Burly Durant at Lincoln CPA Library, Security Administration Office of Earnings Operations FOIA Workshop, Music Information Center of the Chicago Public Library's Harold Washington Library Center, Bureau of Vital Records at Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, the St. Louis and Los Angeles chapters of the American Federation of Musicians, State Historical Society of Missouri, Kansas State Historical Society & Archives, Midwest Genealogy Center & Mid-Continent Public Library, Bill Osment at Kansas City Public Library, Mississippi Blues Trail, Watkins Brothers Memorial Chapel, Blue Ridge Lawn Cemetery and Lincoln Cemetery.

*********************

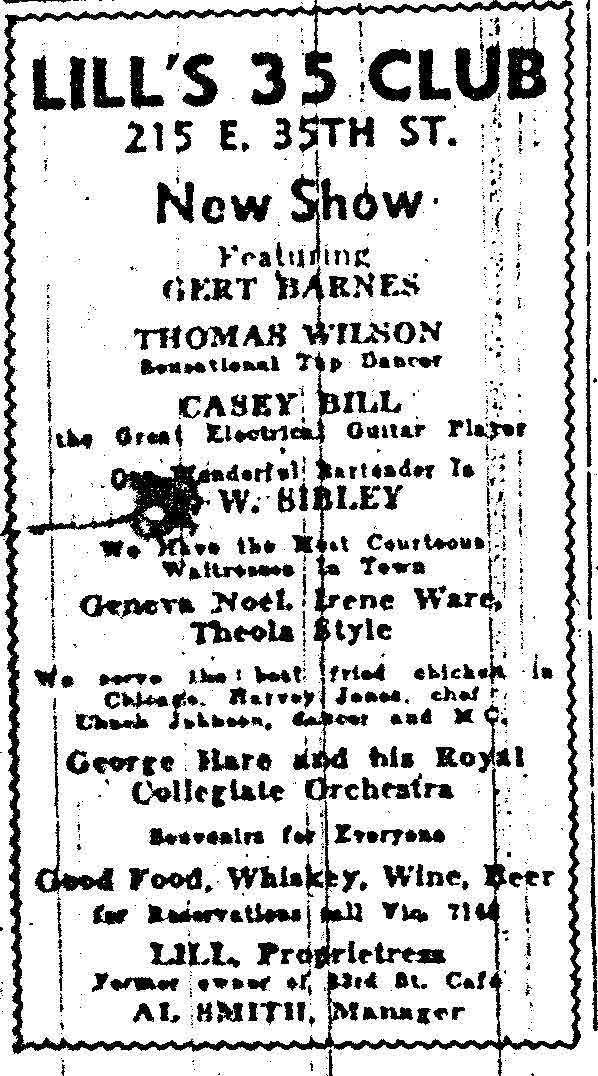

Updates: Since this article was published, more information on Casey Bill has surfaced although many mysteries remain. Bob Riesman and Robert Pruter sent more ads from the Chicago Defender, and one of them, advertising "Casey Bill, the Great Electrical Guitar Player," is from Oct. 9, 1937, making this the earliest ad I have seen so far for a blues artist playing electric guitar. Of additional interest, on the same page of the Defender is a news item noting that Andy Kirk's orchestra had just finished an engagement at another South SIde club, the Grand Terrace. We have no proof, but Kirk and his band may have heard Casey Bill while in town and this may have inspired Kirk to feature electric steel guitar after Floyd Smith joined the group in 1938.